Past Talks : January 2021

“Nihil Obstat – One man’s war in 825 Naval Air Squadron” by Tudor Rees

Nihil Obstat is the motto of 825 Naval Air Squadron (NAS), which our speaker, Tudor Rees, quoted as ‘Nothing Stops Us’, or as the Catholic Church might put it ‘Nothing Hinders’ or ‘Nothing Stands in the Way’. Whichever slant you put on it, the message is clear. Bearing in mind that 825 Squadron was throwing itself against a well-equipped and ruthless enemy, and of course nature itself in the raw Atlantic, its open cockpit Fairey Swordfish biplanes conjure an astonishing picture. But they were most successful and very rightly celebrated. Courage and a rather decent sheepskin suit and helmet were paramount. No room for pampered ‘snowflakes’ in that scenario.

Nihil Obstat is the motto of 825 Naval Air Squadron (NAS), which our speaker, Tudor Rees, quoted as ‘Nothing Stops Us’, or as the Catholic Church might put it ‘Nothing Hinders’ or ‘Nothing Stands in the Way’. Whichever slant you put on it, the message is clear. Bearing in mind that 825 Squadron was throwing itself against a well-equipped and ruthless enemy, and of course nature itself in the raw Atlantic, its open cockpit Fairey Swordfish biplanes conjure an astonishing picture. But they were most successful and very rightly celebrated. Courage and a rather decent sheepskin suit and helmet were paramount. No room for pampered ‘snowflakes’ in that scenario.

This talk was the second presented to members via Zoom on our home computers or ‘phones, and I am much impressed with just how good and absorbing they are. We were treated to the full graphic slide show and an excellent video while Tudor Rees occupied a corner of the screen to give us a ‘voice over’ of the story behind it.

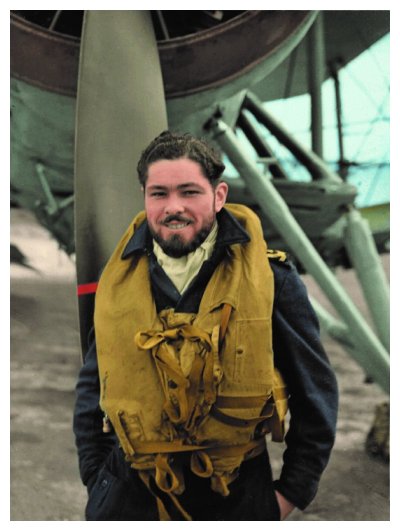

The story today concerned Lt David Rees RNVR, the father of Tudor Rees, our speaker. In the 1940s Tudor informed us that there was no direct recruitment for Fleet Air Arm aircrew, so David Rees completed his School Certificate, and this enabled him to apply for a commission in the RN as an Observer – his first choice. Tudor pointed out that this role was always reserved for commissioned officers, apart from a couple of rare exceptions. Having passed all the initial tests David soon found himself, late in 1941, striding through the gates of HMS St Vincent in Gosport to learn basic seamanship and how to behave like a sailor. Training started on day 1 and once the basics were over the pace quickened and became intense when the actual Observer’s Courses started. Subjects included weapons, navigation, wireless and signals and finally, many months later, flying. At this later stage, part of the day was spent in ground work doing theoretical study on all the numerous elements including the stars, wind, how to find a moving ship, etc. The other part of the day was spent in applying everything learnt in real airborne situations.

An Observer needed to be well equipped with the tools of his trade and these were numerous, cumbersome, but most definitely essential. They would include: a Bigsworth Board for plotting; a lamp for night work; an astro-compass for star readings; a magnetic compass; navigation computers (rather like circular slide rules, not electronic); and several other bits and pieces. On-board the Swordfish itself, the Observer also handled the Air-to-Surface Vessel (ASV) radar, which was not too effective in its early days, but improved significantly later in the war. Sitting in the back of an open cockpit with all this kit it required something of a miracle to get the job done. Remember also that everything in those days was done manually, with achingly numb hands from the cold wind.

Eventually, in late 1942, David Rees was posted to HMS Landrail at Macrihanish to join 766 NAS for Naval Operational Training. It was here that crews ‘crewed-up’ with a pilot and Telegraphist Air Gunner (TAG). Once crewed-up, they always trained and worked together as a team on all aspects, resulting in very strong bonds being formed. By January 1943, David and the crew received their posting to 825 NAS aboard HMS Furious where training continued at a high tempo, including dropping torpedoes at between 100 and 150 feet, more practice on the ASV radar and more practice in using binoculars with some degree of success – very difficult as you can imagine. The Air Wing of Furious comprised nine Swordfish from 825 squadron, nine Fairey Albacores from 822 and nine Seafires from 801 Squadron. By March 1943, HMS Furious formed part of the Home Fleet and by then had a well-seasoned crew. Furious was involved in numerous prominent sorties including the Norwegian campaign and later Operation Husky, the Allied invasion of Sicily. Throughout these operations, 825’s Swordfish carried out anti-submarine sweeps in pairs, searching for the tell-tale wake of a periscope, small as it was, or at the very least keeping the U-boats submerged and out of range. At a depth of 20 ft a submarine is generally invisible, hence non-stop training and practice attacks to keep the crews at a high state of readiness. At one point, storms off Iceland caused three aircraft to break loose in the hangar and to wreck themselves before being secured. Not long after, David Rees was on an anti-submarine patrol with another Swordfish when at the end of the patrol, the two aircraft returned to intercept ‘mother’ (Furious) at the pre-briefed location. To their great dismay, it was apparent that they had both been given ‘duff’ information at their briefing. Furious was nowhere to be seen. Both aircraft continued to search and just when the fuel was about to expire, success, they found the ship, but the weary pilot mis-judged the landing and the aircraft tipped over the side of the deck into the sea. The crew managed to scramble aboard the dinghy and then had to wait a few hours before they were picked up by the destroyer HMS Troubridge. The other Swordfish suffered a similar fate and also crashed, with the crew being rescued in due course. Following a rest David was soon back on operations, this time with a new pilot, because his previous pilot was still recovering from injuries sustained in the crash.

Intense training continued, including a spell at HMS Nightjar at Inskip, Lancashire, to familiarise themselves with new weapons, including rocket projectiles. U-boats had become very heavily armed with batteries of 37mm and 20mm cannon to enable them to remain on the surface and fight off attacking aircraft. This was a formidable retaliation and called for an equally formidable response. The Swordfish were now equipped with four rails under each wing to carry 25lb armour piercing rockets. The rockets were fired in pairs at an angle of around 20°, which allowed the pilot to follow their trajectory, then adjust his aim for the following pair. The effect was said to be like receiving a warship’s broadside and was truly destructive. By 1943 most aircraft were also equipped with ASV radar, which transformed the effectiveness of anti-submarine patrols. Around this time, 825 Squadron pioneered flying night sorties in their Swordfish. At this point we were shown a very lively video showing a Dutch Swordfish three-aircraft flight taking off from and then landing back on a Dutch operated escort carrier. Very gripping stuff putting you right in the driving seat. It was only three minutes long, but packed with action, I loved it.

In August 1943, six Sea Hurricanes joined 825 Squadron, indicating that operations from an Escort Carrier were imminent. Escort Carriers were generally built in the USA and arrived complete with luxuries previously unknown to British sailors. Hopes were high and sure enough the ship, HMS Vindex, was brand-new as an aircraft carrier. That was good news. Not quite such good news was that it had been converted from a merchant hull in Swan Hunter’s yard on Tyneside and had none of the luxuries! A ‘shake down’ period followed, allowing the ship and air crews to familiarise themselves before becoming operational again. Do remember that the average age of aircrew at this time was in the region of 19 to 20 years and they carried so much responsibility.

On 14 January 1944, Lt David Rees experienced his second ditching, once again over the side of the ship. This time he was quickly picked up, returned to the ship and back on operations. Even for these fit young men immersion in the cold sea quickly sapped their strength and they had to be assisted in the rescue. On top of this there was a great deal of tension and frustration due to faulty switches causing weapons failures. It was most galling to risk your neck in an attack and then to have the weapon fail.

As if that was not frustrating enough, David then suffered his third crash into the sea. On this occasion his Swordfish and the one following it off the deck both had engine failure, later established as fuel contaminated with water. Both aircraft crews were picked up promptly by a MSL motor launch and subsequently transported to hospital. For David it was considered that three ditchings were enough and he was posted to 783 RNAS as an instructor. 783 Squadron operated a variety of aircraft including Lockheed Hudson, Avro Anson and Fairey Barracuda in the air signals roles. As you might have noticed, Lt David Rees had become a full-fledged member of the Goldfish Club with three awards in total. He was lucky to survive not only the crash on each occasion, but also the immersion in cold seas where body temperature soon drops below the critical 35° where losing your faculties is just the start of your problems.

In recognition of his father and the other warrior crews of Swordfish aircraft generally, Tudor Rees commissioned a vivid painting by renowned aviation artist Gareth Hector, showing a Swordfish on approach to its carrier – as shown in Jabberwock issue 102. It is a fitting and graphic tribute to these modest heroes who helped to conquer a powerful and unrelenting enemy. Thank you Tudor Rees for a very enjoyable and profusely illustrated talk. I like to think that Nihil Obstat can also be applied to the determination of the SOFFAAM backroom boys for facilitating these splendid talks via Zoom, despite the obstacles presented by the curse of Covid-19. Thank you all.